-

Is Remote Work the Future of Employment?

The global workforce has undergone a profound transformation in recent years, with remote work emerging from a niche practice to a mainstream employment model. Accelerated by technological advancements and global events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, remote work challenges traditional notions of office-based employment. This article explores whether remote work represents a sustainable future for…

-

Should Animal Testing Be Banned Worldwide?

Animal testing has been a cornerstone of scientific research and product development for over a century, yet it remains one of the most controversial practices in modern science. From pharmaceuticals to cosmetics, millions of animals are used in laboratories every year, prompting debates about ethics, necessity, and alternatives. This article explores whether animal testing should…

-

Is Nuclear Energy the Key to a Sustainable Future?

As the world confronts climate change and an urgent need to reduce carbon emissions, energy sources have come under intense scrutiny. Renewable solutions like solar and wind are growing rapidly, but they face limitations in consistency and storage. Nuclear energy, with its ability to produce large amounts of low-carbon electricity, has reemerged as a critical…

-

Should Voting Be Mandatory in Democratic Societies?

Voting is widely regarded as the cornerstone of democracy, yet participation rates vary dramatically across countries and elections. While some argue that casting a ballot is a civic duty that should be compulsory, others view mandatory voting as an infringement on personal freedom. This article examines the debate, weighing the ethical, social, and practical implications…

-

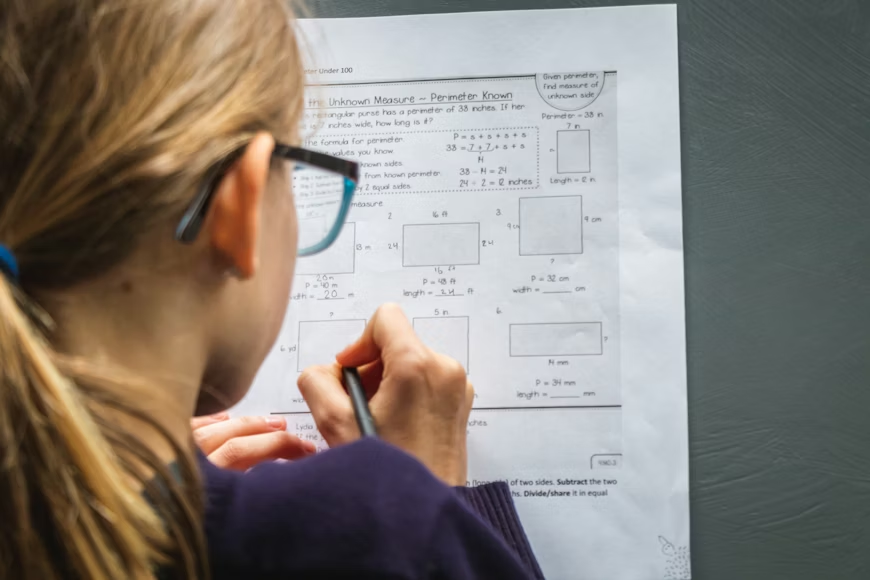

Is Homework Effective or Outdated?

Homework has been part of formal education for over a century, yet few topics divide students, parents, and educators as sharply. Some see it as a critical tool for learning and discipline, while others view it as an outdated practice that adds stress without clear benefits. This article explores whether homework still serves its original…

-

The Ethics of Animal Testing in Medical Research

Animal testing, also known as animal experimentation, has long been a cornerstone of medical research. From the development of vaccines to understanding the mechanisms of diseases, animals have contributed significantly to scientific progress. Yet, despite its undeniable contributions, animal testing remains one of the most ethically contentious practices in medicine. The tension between scientific advancement…

-

Fake News, Social Media, and Critical Thinking in the Digital Era

The rise of digital communication has revolutionized how people consume and share information. Social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter (X), Instagram, and TikTok allow news to travel faster than ever before. Yet this acceleration has created fertile ground for misinformation. Fake news is not new—propaganda, hoaxes, and rumor mills have existed for centuries—but digital technologies…

-

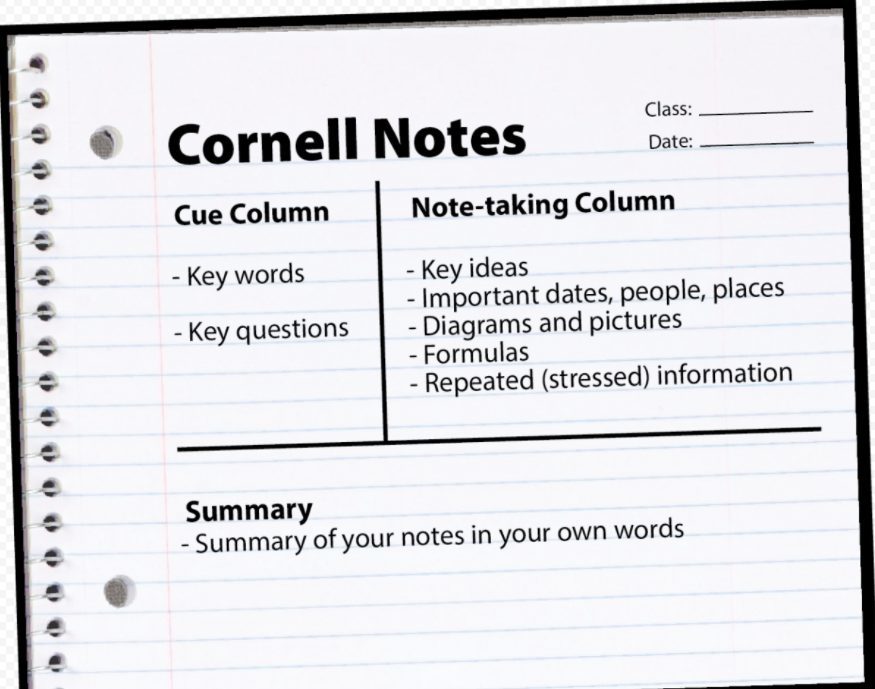

The Science of Note-Taking: Comparing the Cornell Method with Other Techniques

Note-taking has always been one of the most essential skills in education. From the earliest use of wax tablets in ancient Greece to the digital note-taking apps of today, learners have relied on notes to capture, process, and retain information. In the modern world, where information is abundant and attention spans are fragmented, effective note-taking…

-

The Impact of Digital Tools on Modern Education

In the 21st century, digital tools have transformed nearly every aspect of daily life, and education is no exception. The integration of technology into classrooms has redefined the way students learn, teachers instruct, and institutions operate. Digital tools—from interactive software and online learning platforms to tablets and virtual classrooms—have created opportunities for enhanced learning experiences,…

-

The Ethical Implications of Genetic Engineering

Genetic engineering, a branch of biotechnology that involves the direct manipulation of an organism’s DNA, has revolutionized science and medicine over the past few decades. From genetically modified crops to gene therapy and CRISPR-based genome editing, the potential of genetic engineering seems almost limitless. Scientists can now eliminate hereditary diseases, enhance human capabilities, and create…